By Tim Bartik, Aaron Sojourner and Kathleen Bolter

The U.S. Department of Commerce has asked semiconductor manufacturers vying for a share of the $39 billion in incentives from the CHIPS and Science Act to include a strategy for workers who build or operate their plants to access affordable and high-quality child-care services, according to a recent announcement. Is this proposed requirement a good idea? We think the answer is yes—if this requirement leads to broader efforts to promote child-care infrastructure.

The focus on child care as integral “business support infrastructure” could spark a more general change in business attitudes and public policy. Even before the pandemic, the child-care system in the United States was in crisis. Today it is in even worse shape, putting undue pressure on parents—particularly mothers—who too often must choose between balancing unreliable care situations with paid work or dropping out of the labor force entirely. Conservative estimates peg the cost of the nation’s inadequate child-care system at $122 billion in lost earnings and productivity every year, and that’s just for infants and toddlers.

Child-care workers are some of the lowest-paid professionals in the country and seldom receive benefits such as health care or retirement payments as part of their job. Parking lot attendants and animal caretakers get higher wages per hour than those who care for our young children. Without concerted efforts to increase the quality and compensation of these jobs, the root causes of a shortage of child care workers will not be addressed. But increasing the cost of child care to pay child-care workers more and provide better benefits is a difficult proposition if parents and guardians are expected to shoulder the full cost.

Across the country, the cost of center-based child care is higher than the cost of in-state tuition at a public four-year university. High-quality centers generally cost even more. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services defines affordable child care as costing less than 7 percent of income; however, recent surveys have found that more than half of families spend 20% or their income or more on child care. Finding solutions to such a large-scale problem requires a coordinated approach. The rules put forth by the Commerce Department leave plenty of room for implementing such an approach.

The Commerce Department is requiring that child care be conveniently located and offer hours that will accommodate working parents. It must be accessible to low- and medium-income families and should offer a safe and healthy environment that families can rely on. Under these provisions, there is a high degree of flexibility for how different companies and local areas might build their proposals to receive federal incentives. This creates both risks and opportunities for the communities hosting these plants.

The risks primarily stem from individual semiconductor manufacturers trying to implement solutions alone. Although businesses could potentially either build their own child-care centers, pay to have existing centers expand their operations, or directly subsidize child-care costs, expecting these large anchor employers to be the only businesses providing child care could potentially end up harming other businesses and workers by luring child-care workers from other child-care centers by making attractive bids. In addition, if only semiconductor manufacturers provide child care, and only for their own workers, this limits the potential mobility of their workers to move to other employers. Effecting such a limitation should not be the goal of public policy. Where a big plant opens, employers in its supply chain and local retailers will also tend to open and expand.

Superior solutions exist, but those solutions require a coordinated approach among employers, economic development professionals, workforce developers, educators, and child-care businesses. Better solutions will address the local workforce’s challenges of gaining access to care in general, rather than just those of one particular employer. This ensures that the use of funds is governed by a broader set of stakeholders, including state and local government, labor organizations, and the local care service sector. Better solutions direct funds to state and local communities to supply not only a greater number of care services, but care that is of a higher quality and more affordable, to all families in the community.

So, what are some effective strategies for addressing child care that businesses should adopt in their bid for semiconductor incentives? Policies that lead to broader efforts to promote child-care infrastructure and make child care more accessible community-wide are the most effective strategies.

One strategy that could be successful is for grant-seeking employers to enter into community-benefit agreements to articulate specific strategies for how the benefits of the public subsidy will be maximized and shared. For example, the Commerce Department could look favorably on applications for incentives from semiconductor manufacturers that propose to contribute to community-wide funds for child care, which would go beyond merely assisting their own workers. Creating the infrastructure to manage such funds will be important in the implementation.

In their attempt to leverage the semiconductor incentives to build broader clusters, state and local governments could try providing sustainable funding for better child care for the entire community. One possible mechanism for sustainable funding is the creation of tax increment financing districts, under which a portion of the increased property-tax revenue or other revenue in a designated local cluster area could be used to pay for needed infrastructure improvements, including child care.

States and local governments could also appropriate funding to expand models like Michigan’s MI Tri-Share system, in which the cost of child care is divided equally between employees, employers, and the state. Programs such as this help subsidize the cost of providing high-quality child care more broadly within the community. Expanding access to child care among all employers would benefit workers by freeing them from dependence on a single employer, thus increasing their ability to pursue competing employment opportunities, and potentially giving workers better bargaining power with employers.

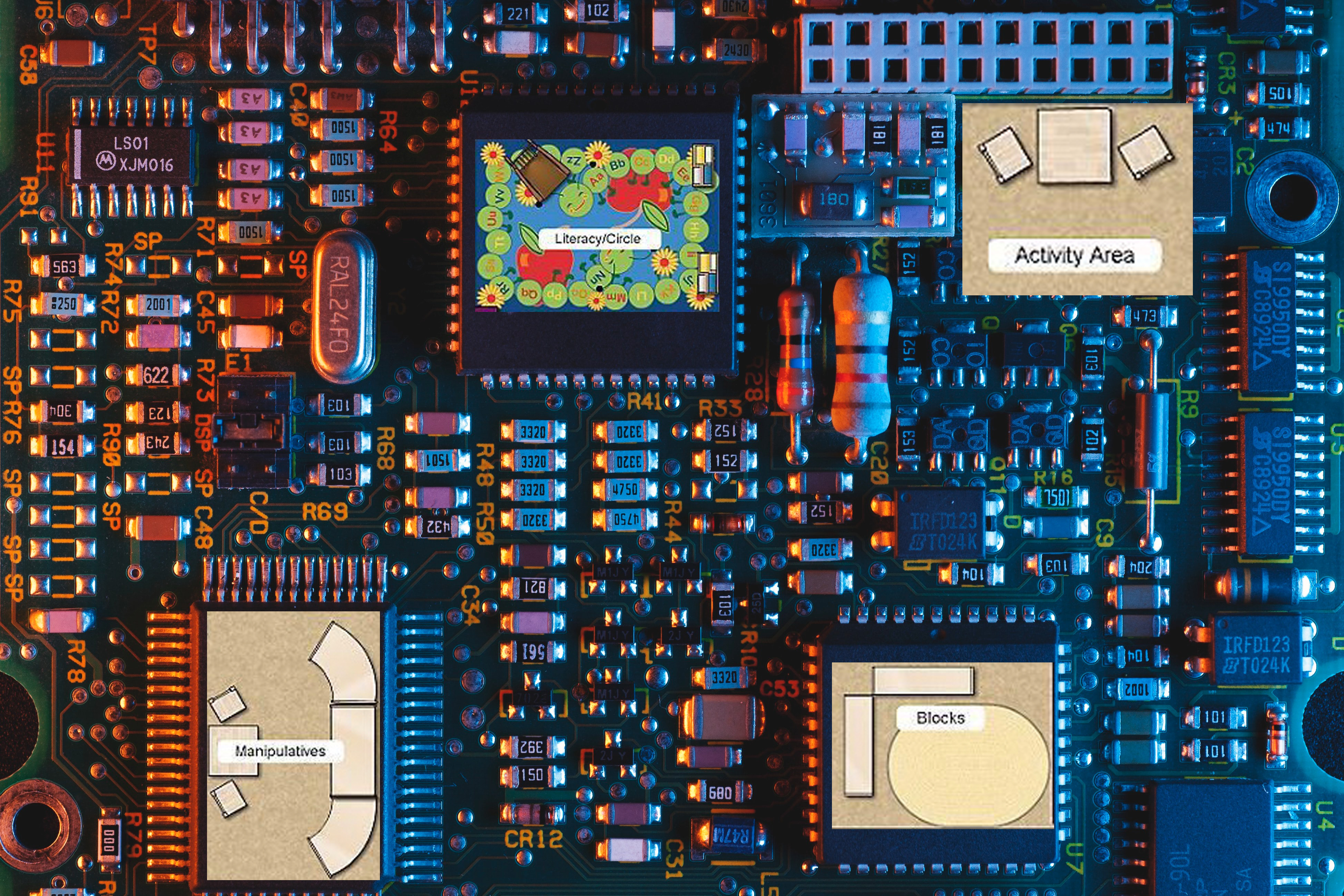

The semiconductor incentives are meant to spur the development of new American economic clusters and produce thriving local economies. When a large employer arrives in a community, filling those jobs often requires attention by the community to improving and expanding a variety of systems, including local child care, K–12 education, transportation, and housing. State and local policymakers can complement the requirements for semiconductor manufacturers with increased support in these local economies for all local families and all local workers. Sizable increases in local support of child care for all workers in a community can help ensure that the growth in semiconductor manufacturing spurred by the CHIPS Act leads to truly inclusive growth for all of a community’s population.